Cheltenham United Methodist Church

June 14, 2020

Genesis 18:1–15; 21:1–7; Matthew 9:35–10:15

I. BEGINNING

I forget what the joke was, exactly. But it was at the Monday morning knitting-group and I’m reasonably sure it was at my expense, though in a good-natured kind of way. Whatever the joke was, the commentary was swift and sure: “Well, that’s how you know—you’re one of us now.”

That’s a comforting thing to hear as a new pastor. It’s nice to know that you’ve been accepted. And our lives are filled with such rites of belonging, those moments when you know that you’re truly welcomed in a place.

That it should happen in church should not be surprising. I have rarely gone to a Methodist church and not felt welcomed. Once, in college, I attended services at McKownville United Methodist Church. They were so friendly to me that one of them even wondered whether they’d scared me off for good. I didn’t go back there, but it had nothing to do with their friendliness and more to do with the schedule I kept in college which was not conducive to Sunday morning piety.

It’s encouraging to see that so many of our churches are welcoming spaces, because welcome is at the heart of our Christian values.

II. THE TEXT: THE IMPORTANCE OF HOSPITALITY

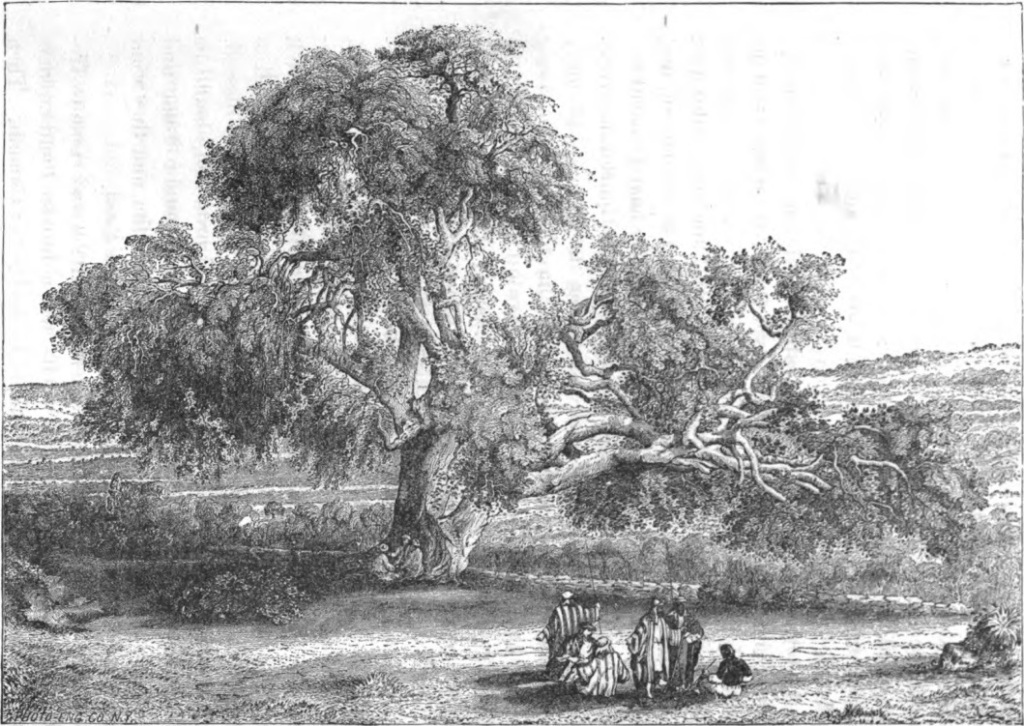

We certainly see it on display in the two texts we heard read this morning. The first is from Genesis and tells the story of three strangers who come to visit Abraham as he is encamped near the oaks of Mamre. Abraham looks up, notices the men, and without any knowledge of who they are, runs to meet them, bows down before them and says, “

“My lords, if I find favor with you, do not pass by your servant. Let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree. Let me bring a little bread, that you may refresh yourselves, and after that you may pass on—since you have come to your servant.”

When they agree, Abraham leaps into action:

And Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Make ready quickly three measures of choice flour, knead it, and make cakes.” Abraham ran to the herd, and took a calf, tender and good, and gave it to the servant, who hastened to prepare it. Then he took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them; and he stood by them under the tree while they ate.

The demonstration of hospitality and welcome here is powerful. The visitors are fed cakes made from “choice flour” and fed them a calf “tender and good” along with curds and milk, feeding them and standing ready to offer more should they need it.

It is a stunning display of welcome and hospitality, especially since Abraham does not yet know who these three visitors are. The fact that they are God and two angels has not yet been revealed before Abraham leaps into action.

His generous and extravagant hospitality is also drawn in contrast to the story that happens in the very next chapter. The two angels are sent to investigate the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, to see if the complaint about them is true. As the angels arrive, they are greeted by Lot who, like Abraham, rises to meet them, bows down, and invites them to stay with him. They demur and say they’ll stay in the square, but Lot’s hospitality, like that of Abraham’s is insistent.

The people of the city, however, are not so welcoming. They seek to do violence to Lot’s visitors and then to Lot himself for objecting to their wickedness. The angels help Lot to flee the city before it is destroyed. The contrasting expressions of hospitality and welcome with Abraham and Lot on one hand and Sodom and Gomorrah on the other make clear the dire consequences of inhospitality. Indeed, this lack of hospitality and care seems to have been central to the crimes of Sodom and Gomorrah. The prophet Ezekiel writes, “This was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease, but did not aid the poor and needy.” (Ezekiel 16:49 NRSV)

And Jesus himself seems to make this connection between the sin of the cities of the plain and the lack of hospitality. In the passage from Matthew’s gospel we read earlier, Jesus is sending his disciples out on a mission to preach, teach, heal, cast out demons, cure lepers, and proclaim the kingdom of heaven, with minimal provisions. He gives them this instruction:

“Whatever town or village you enter, find out who in it is worthy, and stay there until you leave. As you enter the house, greet it. If the house is worthy, let your peace come upon it; but if it is not worthy, let your peace return to you. If anyone will not welcome you or listen to your words, shake off the dust from your feet as you leave that house or town. Truly I tell you, it will be more tolerable for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah on the day of judgment than for that town.”

For those towns and places that do not practice hospitality, that do not welcome the disciples on their journey, they shall be judged even more harshly on Judgment Day than Sodom and Gomorrah, the paragons of inhospitality.

We see then that hospitality is not merely the by-product of Ancient Near Eastern cultures (as it remains today in Middle Eastern cultures), but is an essential element of Christian faith. One cannot be a Christian, it seems, and not be welcoming.

III. MORE THAN WELCOME

I have always pastored welcoming congregations. By that I mean, of course, every congregation has said how welcoming they are. None of them, at least not while I was with them, ever said, “We’re good. We don’t want anyone else to join us. In fact, we wish they’d stay away.” No, every congregation has expressed a real desire to welcome new people.

Whether the people they sought to join them felt the same way is a different question.

For example, when I first started working on a college campus, the United Methodist community was fairly small. As one of the students would quip, “Sometimes we have more people in the choir than people they’re singing to.” What this meant was that a fairly small number of people could run the community, and that’s what wound up happening. There were four or five students who were in charge of everything. The problem was that visitors to the community figured this out right away. They figured out that it was this small group of folks who were in charge and unless you belonged to that group, you were likely never going to get to have any meaningful involvement beyond participation.

Now, I can say with great assurance that there was not a person in the group who was seeking to shut out anyone from the reins of power in that community. It was a by-product of small communities in which close, intimate relationships among the leaders develop. Somewhat as a Catch-22, the only way to break that pattern is to get more people involved, but so long as that pattern is in place it’s hard to get more people involved.

But what it demonstrates is the fundamental difference between welcome and inclusion. Anyone can feel welcomed when they come to a new faith community for the first time, but will they be included? Will they feel that they belong? Those are different questions.

Creating communities not only of welcome, but of inclusion makes the work of hospitality real. We’re more than just a business in the hospitality industry. We’re more than just a hotel or a restaurant. Because we’re expected to be more than just a nice place to visit; we’re expected to be a community of faith. And for a community to thrive, its members have to feel that they are more than welcomed. They have to feel that they belong. There has to be a sense of ownership.

A. Belonging

A few years ago, I had occasion to visit portions of the West Bank for a friend’s wedding. I spent a few days in Jericho and from there we visited Ramallah, Bethlehem, the Dead Sea, and I even got a chance to visit Jerusalem for a couple of hours, albeit without my friends. At one point as we traveled, we came across a checkpoint in the middle of nowhere. It was not at a border crossing or near an Israeli settlement. I asked about it and was told, “It’s here because they can put it here. Everything they do is to remind us that it’s their country. They just let us live here.”

This helped me to understand the behavior of a man we’d met in Bethlehem. He was the proprietor of an olive wood carving shop right down the street from the Church of the Nativity. He was one of many Palestinian Christian families who had lived in Bethlehem for centuries. And how did we come to know that? Because he had the documentation to prove it right in the drawer near the cash register where we stood. Now, I suppose that, if pressed, I could come up with a copy of my great-grandfather’s immigration records from 1901 when he arrived from Stuttgart. And I could come up with family records that show that my maternal ancestors were among the original thirteen families of Rhode Island. I’m sure a lot of this stuff is already tagged on my account at Ancestry.com. But I cannot imagine having to have that paperwork on hand with me all the time just to prove that I belong in the only home I’ve ever known.

Being present and being allowed in a space is not the same as being included. It’s not the same as belonging.

B. Racial Justice

I imagine that a lot of our Black and brown brothers and sisters are feeling this way and have been for a long time. It has long struck me as odd that the overwhelming majority of African Americans descend from those forcibly brought here before 1809, well before the great waves of immigration that brought folks like my paternal ancestors here in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. And yet, somehow, Black Americans are constantly having to prove their Americanness to the rest of us. Shouldn’t it be the other way around? It reminds me of something a friend of mine used to say, “We’ll never get anywhere until White Americans accept that Black Americans are Americans.”

So many of the cries for justice that we have heard across the decades and amplified in these recent weeks are out of a frustration that Black Americans have never truly been included. That they are living under a system that serves to remind them that this country belongs to those of us who are white; we just let them live here.

C. Justice and Hospitality

And so, we come to understand that the work of racial justice and equality are not just expressions of Christian values of justice and the Social Gospel, but they are expressions of what is called the beloved community. The work of inclusion is not simply about equal access, it’s about equal belonging. It’s about real, authentic community in which everyone is recognized as a part.

Hospitality is more than having an open tent; it’s having a big tent where all are treated as children of God, made in the image of God. Where all have a seat at the table.

But there are reasons for doing so that go beyond simple mandate or simple Christian charity.

IV. THE FRUIT OF HOSPITALITY

The visit to Abraham at the oaks of Mamre was far more than just an occasion for welcome and hospitality. It was not just an opportunity for socializing with God and two angels. It was an opportunity for blessing.

See, at the beginning of Abraham’s story, six chapters earlier, he had been told before he set out that if he left his country, his kindred, and his father’s house for a land that God would show him, there God would make of him a great nation and a blessing to all the families of the earth. Implicit in that promise is the promise of descendants—children from whom a “great nation” might come.

At times Abraham and Sarah took this promise into their own hands, such as when Sarah offered her handmaid Hagar to Abraham for the purpose of bearing an heir for him, leading to the birth of Abraham’s first son, Ishmael. Now, they certainly might have been forgiven for thinking that if Abraham were indeed to become the father of a “great nation” at his and Sarah’s ages, they were going to have to take action themselves.

And yet, here, at the Oaks of Mamre, after having welcomed the three strangers into his tent and shown lavish hospitality, he receives news of blessing beyond his ability to comprehend: his wife Sarah will indeed have a son. The news is so astounding and incomprehensible that Sarah even laughs aloud at the idea. (When the promise is fulfilled and Abraham’s son is born, the name they give him—יצחק Yitzhaq “Isaac”—means “he laughs.”) But it is in the creation of a space of hospitality and welcome that Abraham and Sarah receive blessing beyond imagining. And through them, as was promised, we, too, receive blessing.

In the same way, the towns to which the disciples are sent on their mission that show hospitality and welcome will receive blessing: curing of the sick, raising of the dead, cleansing of lepers, casting out of demons, and the proclamation of the gospel that “the kingdom of heaven has come near.”

Imagine being one of those who received the disciples on their wandering. Imagine having a family member with a severe illness, or someone with a great affliction, and then after welcoming two strangers into your home as an act of hospitality, having that loved one cured or their affliction banished, and then hearing that these things were a sign of God’s victory over evil and death. That the kingdom of God was at hand. Would this not be blessing beyond imagining?

But this is the fruit of hospitality: blessing in ways that we would never have expected.

V. END

We often think that hospitality and inclusion are meant to benefit the people who are welcomed or who have been previously excluded. There is some truth to that, especially if there is some benefit to the group of which we are a part, like the bar association, the chamber of commerce, the United States Senate, or something.

But what goes overlooked is the tremendous opportunity for blessing for us. Abraham and Sarah welcomed the strangers and found themselves blessed with news of a son they would never have expected. Those who received the disciples welcomed strangers and found themselves blessed in ways that they could never have imagined and that were transformative of their lives and of their world. Why should it be otherwise for us?

One of the great tragedies of contemporary Christianity is the number of people who do not even try to come to a worship service or other event of the church because they feel they will be unwelcome. That they do not belong. So much so that when we think of hospitality, it is often framed as granting access to the gifts we possess to those who have been denied them.

But is it not also the case that it is we who have been denied the gifts of those who have been excluded? How many gifted women preachers did the church lose out on before deciding to ordain women in the 1950’s? How many gifted leaders of color did the church lose out on because of the segregation that it did not end until 1968? How many gifted preachers and church leaders is the church now losing out on because of their orientation or gender identity?

What blessings are we denying ourselves when we fail to rush to greet the strangers at the entrance of our tents? What blessings have we forsaken when we turn away the traveling pair who shake the dust of our churches off their feet as they depart? How much do we claim to be the New Jerusalem with gates that are never closed, but in reality are Sodom and Gomorrah?

This work, like all the work of the gospel, isn’t easy. It’s hard when you’re already on the inside to imagine what it’s like being on the outside. It’s hard to imagine what the barriers might be, what the obstacles to welcome and inclusion might be. But that is the work we are called to.

But we are not alone in this work. The God who stood outside Abraham’s tent stands outside ours even now. The Christ who sent his disciples out with authority gives us the grace to receive him in those we meet. The Spirit who empowered the apostles to translate the gospel into new contexts, empowers us to hear anew the Word of God from new and powerful voices.

We have the grace we need for the task before us.

For right now, the strangers stand outside the entrance to our tents, ready to extend blessing. Will we let them in?

The Text

Genesis 18:1–15; 21:1–7 NRSV • The Lord appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the entrance of his tent in the heat of the day. He looked up and saw three men standing near him. When he saw them, he ran from the tent entrance to meet them, and bowed down to the ground. He said, “My lord, if I find favor with you, do not pass by your servant. Let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree. Let me bring a little bread, that you may refresh yourselves, and after that you may pass on—since you have come to your servant.” So they said, “Do as you have said.” And Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, “Make ready quickly three measures of choice flour, knead it, and make cakes.” Abraham ran to the herd, and took a calf, tender and good, and gave it to the servant, who hastened to prepare it. Then he took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them; and he stood by them under the tree while they ate.

They said to him, “Where is your wife Sarah?” And he said, “There, in the tent.” Then one said, “I will surely return to you in due season, and your wife Sarah shall have a son.” And Sarah was listening at the tent entrance behind him. Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in age; it had ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women. So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, “After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I have pleasure?” The Lord said to Abraham, “Why did Sarah laugh, and say, ‘Shall I indeed bear a child, now that I am old?’ Is anything too wonderful for the Lord? At the set time I will return to you, in due season, and Sarah shall have a son.” But Sarah denied, saying, “I did not laugh”; for she was afraid. He said, “Oh yes, you did laugh.”

The Lord dealt with Sarah as he had said, and the Lord did for Sarah as he had promised. Sarah conceived and bore Abraham a son in his old age, at the time of which God had spoken to him. Abraham gave the name Isaac to his son whom Sarah bore him. And Abraham circumcised his son Isaac when he was eight days old, as God had commanded him. Abraham was a hundred years old when his son Isaac was born to him. Now Sarah said, “God has brought laughter for me; everyone who hears will laugh with me.” And she said, “Who would ever have said to Abraham that Sarah would nurse children? Yet I have borne him a son in his old age.”

Matthew 9:35–10:15 NRSV • Then Jesus went about all the cities and villages, teaching in their synagogues, and proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and curing every disease and every sickness. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion for them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore ask the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.”

Then Jesus summoned his twelve disciples and gave them authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to cure every disease and every sickness. These are the names of the twelve apostles: first, Simon, also known as Peter, and his brother Andrew; James son of Zebedee, and his brother John; Philip and Bartholomew; Thomas and Matthew the tax collector; James son of Alphaeus, and Thaddaeus; Simon the Cananaean, and Judas Iscariot, the one who betrayed him.

These twelve Jesus sent out with the following instructions: “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel. As you go, proclaim the good news, ‘The kingdom of heaven has come near.’ Cure the sick, raise the dead, cleanse the lepers, cast out demons. You received without payment; give without payment. Take no gold, or silver, or copper in your belts, no bag for your journey, or two tunics, or sandals, or a staff; for laborers deserve their food. Whatever town or village you enter, find out who in it is worthy, and stay there until you leave. As you enter the house, greet it. If the house is worthy, let your peace come upon it; but if it is not worthy, let your peace return to you. If anyone will not welcome you or listen to your words, shake off the dust from your feet as you leave that house or town. Truly I tell you, it will be more tolerable for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah on the day of judgment than for that town.”